This year marks the sixtieth anniversary of The Letter from a Birmingham Jail.

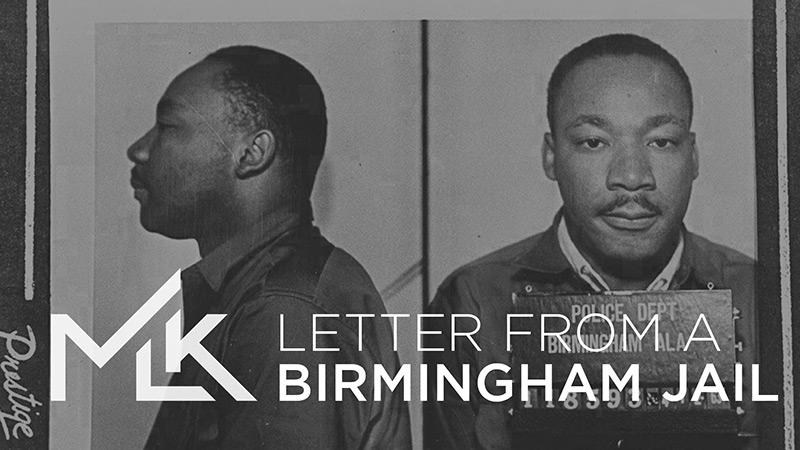

This letter came about in April 1963, after Martin Luther King, Jr. was arrested while participating in a campaign to desegregate Birmingham, Alabama.

A group of clergymen responded to the Birmingham demonstrations by publishing an open letter in the newspaper. This letter called the protests “extreme measures” which were “unwise and untimely” and which could “incite to hatred and violence.” The clergymen suggested that race questions should be resolved in court, not in the streets, and in the meantime current law should be obeyed, to preserve law and order.

From his jail cell, King wrote a response challenging the “white moderate” and calling people to creative nonviolent action for the cause of racial justice. He scribbled his letter on paper towels, newspapers, and eventually pieces of stationery which his attorney, Dr. Clarence Jones, smuggled out of the jail during their daily visits. What at first seemed like an “indistinct jumble of biblical phrases wrapped around pest control and garden club news” became one of King’s most significant pieces of writing. His words to the American church still resonate sixty years later.

We share excerpts here. To read the full letter, visit Stanford University’s online collection of MLK’s papers at kinginstitute.stanford.edu.

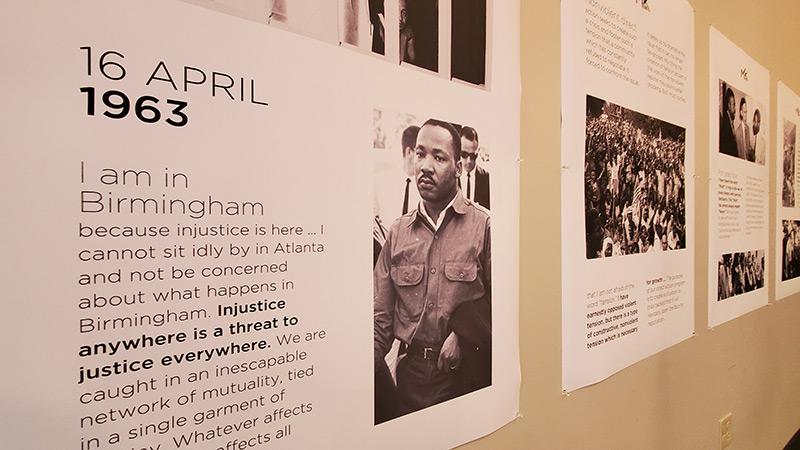

Letter from a Birmingham Jail

16 April 1963

I am in Birmingham because injustice is here … I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly…

Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth … The purpose of our direct action program is to create a situation so crisis packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation…

For years now I have heard the word “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

We have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and God given rights. The nations of Asia and Africa are moving with jetlike speed toward gaining political independence, but we still creep at horse and buggy pace toward gaining a cup of coffee at a lunch counter…

I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice…

I have not said to my people: “Get rid of your discontent.” Rather, I have tried to say that this normal and healthy discontent can be channeled into the creative outlet of nonviolent direct action. And now this approach is being termed extremist. But though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.”

So often the contemporary church is a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound. So often it is an archdefender of the status quo. Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church’s silent–and often even vocal–sanction of things as they are….

I hope this letter finds you strong in the faith. I also hope that circumstances will soon make it possible for me to meet each of you, not as an integrationist or a civil-rights leader but as a fellow clergyman and a Christian brother. Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear drenched communities, and in some not too distant tomorrow the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all their scintillating beauty.

Yours for the cause of Peace and Brotherhood, Martin Luther King, Jr

Thank you for posting this! It never gets old. I learn something new each time I re read it.